Making Meaning in a Meaningless Time

I’ve been thinking about emotion, that sometimes irrational energy that lives and sleeps under our skin. And I’ve been thinking about how can we elicit emotion to create connection and meaning and empathy and resonance, both as writers and humans.

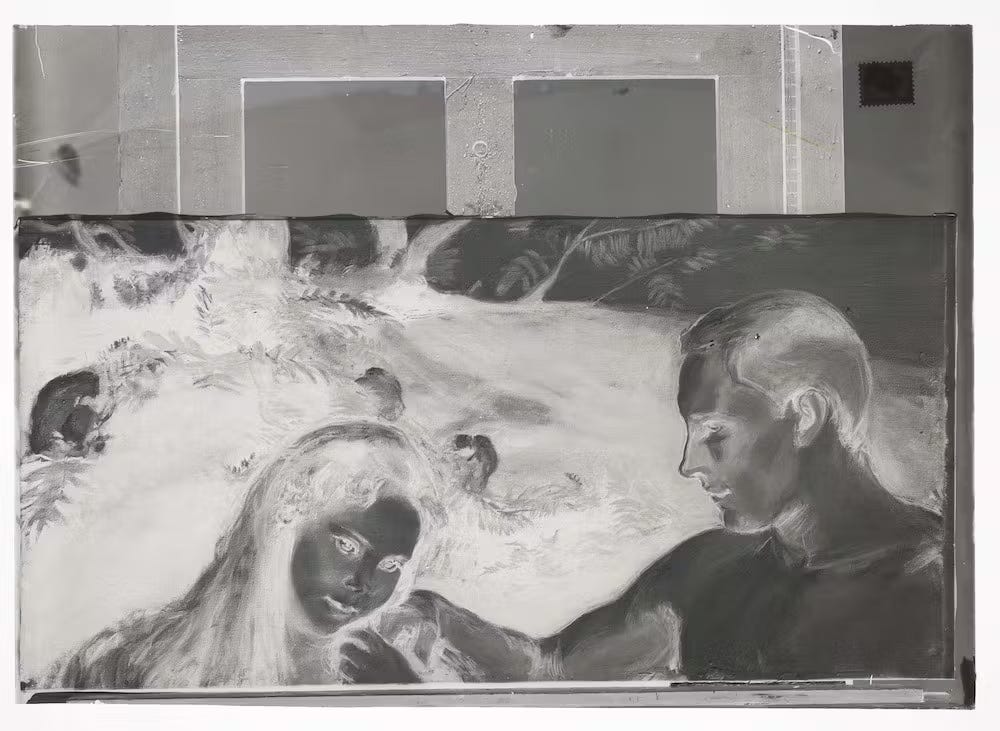

Magnus Enckell, The Lovers, ca. 1904, oil on canvas, owner unknown. Glass negative, dry plate.

So often naming something is liberating. Saying or writing, “I am angry at [fill in the blank]” externalizes a tight, stuffed up, oppressive feeling and sets it free. Externalizing hard emotion is of course the foundation of therapy, and can be endlessly useful.

But I’ve been thinking about the opposite, how best to offer up words and story that harness something greater than black symbols on a white page. How do we place these symbols together in such a way that they do not slide past our readers’ eyes, given the multitude of information that floods them every moment? How do we say or create things that land inside other people and ideally even awaken us and them? How, essentially, do we connect more effectively with readers and with people in general?

Creating meaning and resonance both within the writer and the reader is often not a matter of using direct language. It’s a matter of tapping into something more oblique and strange, something I think of as nearly primordial. Often doing so is accidental. The act of trying too hard places metal scaffolding around something ethereal.

Beginning writers are taught to rely on the five senses in order to bring a story to life. In my tenure at The Best American Short Stories, I read an endless number of stories that kicked off with all five senses. It’s not the inclusion of these senses that’s problematic— it’s the roteness with which they are too often recounted (see as problematic the verbs “is,” “smell,” “sounded,” etc.), as if a new writer is checking off a task on a list without slowing down long enough to inhabit it.

I cannot advocate loudly enough for weird language. For bold language, words that surprise, ideas that come through you, not from you. A good way to access this part of your soul is to write quickly, allow yourself that shitty first draft. If you time yourself and write for ten minutes, maybe you’ll end up with a paragraph or two. Much of it might be messy nothingness, but there may be one or two words in there that will lead you toward a portal you did not know existed.

I am writing this on Cape Cod, where I’m staying with a friend and working on a novel. I have two books with me, and so randomly, here are two very different examples of what I mean by tapping into the reader’s subconscious:

“When you wet the bed, first it is warm and then it gets cold. His mother put on the oilsheet. That had the queer smell. His mother had a nicer smell than his father. She played on the piano the sailor’s hornpipe for him to dance. He danced.” -A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, James Joyce

“For the first time in her life, she’d taken to wearing pantyhose, and not just one pair but two, along with black compression socks. It wasn’t a great look, but she felt the need to be held, squeezed…When she removed the socks: remote sadness, nothing serious. This upset people (her fiancé), who expected visible signs of distress (inconsolable sobbing), especially given her mother’s suicide when Greta was thirteen…” -Big Swiss, Jean Beagin

Here are veeeery different books, but two moments equally moving to me about the enormous influence of mothers. These are “show, don’t tell” moments, and I suppose that “show, don’t tell” is a great rule for a writer when the writer wants to evoke emotion. But telling can be just as useful if used with intent and honestly.

What frightening and relentless times these are. I’ve tried to slow down when I can and both watch for and create meaning. A surprising sentence or two in a client’s work, a friend confessing to “quiet quitting” her relationship, deciding that one of my characters who feels impotent should choke on and then be rescued from a crumb of biscotti: these weird little moments when language not only matches but elevates the things it describes have struck me lately. These moments have all but saved me, as they’ve reminded me that we still have the power to fill or lighten or move ourselves and others.

Albert Edelfelt, Summer evening, 1883, oil on canvas, owner unknown. Glass negative (and positive), dry plate, 385 x 335 mm, Daniel Nyblin ca. 1883.

(More of these images of glass negatives and other wonders can be found in The Public Domain Review, a treasure trove of found words and images.)